Introduction

In the modern world, we see medicine as a field of hard science and palmistry as a form of esoteric entertainment. But in the ancient world, particularly in the time of the Greeks and Romans, the line between the two was not so clearly drawn. Physicians like Hippocrates and Galen pioneered a holistic system of medicine centered on the theory of the Four Humors, which governed a person’s health and temperament.

Interestingly, the hand was often considered a valuable diagnostic tool in this system. For these ancient doctors, the features of the palm—its color, texture, and the quality of its lines—were not for predicting the future, but for assessing the present: the physical and psychological balance of their patient. This is the story of medical chiromancy, a fascinating intersection of ancient science and the art of hand analysis.

The Theory of the Four Humors

To understand how the hand was used in medicine, we must first understand the Four Humors. This theory, which dominated Western medical thought for over 2,000 years, proposed that the human body was filled with four basic substances, or “humors.” A healthy person had these humors in perfect balance. Illness, both physical and mental, was the result of an imbalance—an excess or deficiency of one of them.

The Four Humors and their associated temperaments were:

- Blood (Sanguine): Associated with the Air element. A sociable, optimistic, and cheerful temperament.

- Yellow Bile (Choleric): Associated with the Fire element. An ambitious, passionate, and sometimes aggressive temperament.

- Black Bile (Melancholic): Associated with the Earth element. An introspective, analytical, and often sad or anxious temperament.

- Phlegm (Phlegmatic): Associated with the Water element. A calm, thoughtful, and peaceful temperament.

An ancient physician’s primary goal was to identify which humor was out of balance and prescribe treatments (like diet, herbs, or lifestyle changes) to restore equilibrium.

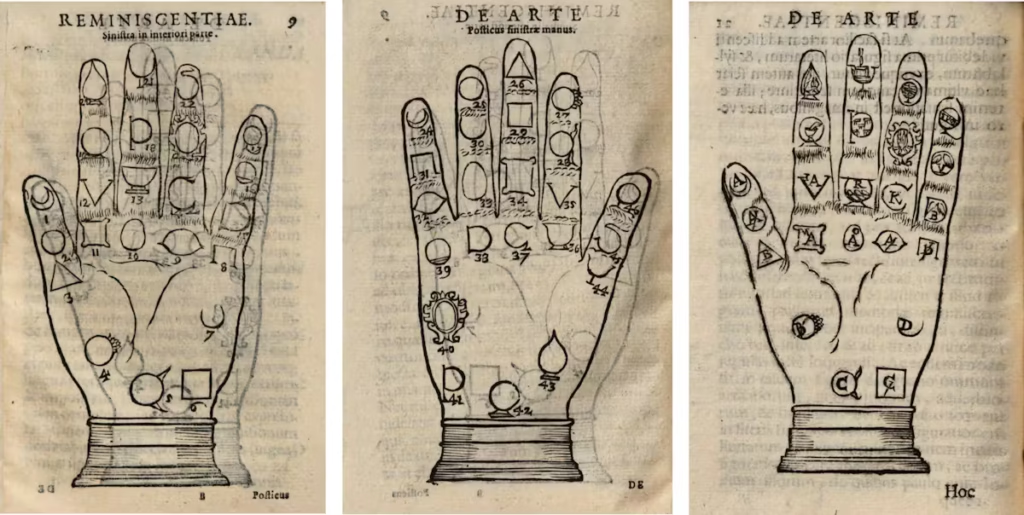

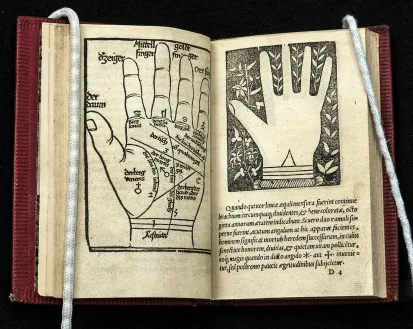

The Hand as a Diagnostic Chart

So, where does the hand fit into this? Ancient medical practitioners believed the body was a unified whole and that the state of one’s inner health would manifest externally. The hands, being richly supplied with nerves and blood, were seen as a particularly clear window into a person’s humoral balance.

A physician examining a patient’s hand would look for clues:

- For a Sanguine (Blood) Temperament: They would look for a fleshy, warm, and pinkish palm with well-defined lines. The hand would feel energetic and full, suggesting good circulation and a cheerful, vital nature. An overly red palm, however, might indicate an excess of blood, leading to high-spirited but potentially indulgent behavior.

- For a Choleric (Yellow Bile) Temperament: A firm, hot, and reddish or yellowish-tinged palm would suggest a choleric nature. The lines might be deep and strong, and the hand shape often corresponded to the "Fire Hand" (long palm, short fingers), indicating an individual full of energy and ambition. An excess of yellow bile might manifest as a very dry, hot hand, signaling a person prone to anger and impatience.

- For a Melancholic (Black Bile) Temperament: This temperament was associated with a cool, dry, and thin hand, often corresponding to the "Earth Hand" (square palm, short fingers). The skin might be rougher, and the lines numerous and complex, reflecting the analytical and worried nature of the melancholic. An excess of black bile was thought to make the hand appear pale and bony, a sign of a thoughtful but potentially depressive individual.

- For a Phlegmatic (Phlegm) Temperament: A soft, cool, and moist palm was the classic sign of a phlegmatic person. The hand would often be pale, and the lines less deep, reflecting a calm, gentle, and somewhat passive nature. This corresponds closely to the "Water Hand" (long palm, long fingers). An excess of phlegm might be diagnosed if the hand was excessively soft and clammy, suggesting a person who could be sluggish or emotionally withdrawn.

Conclusion: A Holistic Vision of Health

This ancient practice reminds us that the separation between different fields of knowledge is a relatively modern invention. For the founders of Western medicine, examining the hand was a logical extension of their holistic philosophy. It was a way to quickly and non-invasively gather clues about a patient’s fundamental constitution.

They were not looking for a “marriage line” or a “money line.” They were looking for signs of balance and imbalance, of warmth and coolness, of dryness and moisture. In the hand, the ancient physician saw a map of the body’s internal landscape, a vital tool in the timeless art of healing.