Introduction

When we think of Roman divination, we often picture augurs interpreting the flight of birds or priests examining the entrails of sacrificial animals. Yet, among these state-sanctioned practices, the more personal and intimate art of chiromancy, or palmistry, held a subtle but significant place in Roman society. Imported from the Hellenistic world, which in turn had inherited it from older civilizations, palmistry in Rome was a tool used by emperors, generals, and common citizens alike to gauge character and navigate their formidable world.

While not as formalized as other Roman methods of divination, the study of the hand was seen as a practical way to understand an individual’s nature—their virtues, flaws, and inherent luck. Let’s explore how the pragmatic and powerful Romans viewed the lines etched in their palms.

From Greece to the Heart of the Empire

Palmistry arrived in Rome as part of a larger package of Greek cultural and philosophical imports. The Romans, ever the masters of adaptation, took the foundational principles laid down by Greek thinkers and applied their own practical mindset to them. Figures like Aristotle were believed to have studied the hand, lending the practice an air of intellectual credibility.

For the Romans, a person’s physical form was a direct reflection of their inner character. A strong jaw signified a resolute will, a high forehead suggested intelligence, and similarly, the lines and shape of the hand were believed to be an unalterable signature of one’s innate temperament. This was less about predicting a specific future and more about assessing the raw material of a person’s character.

Julius Caesar and the Mark of a Leader

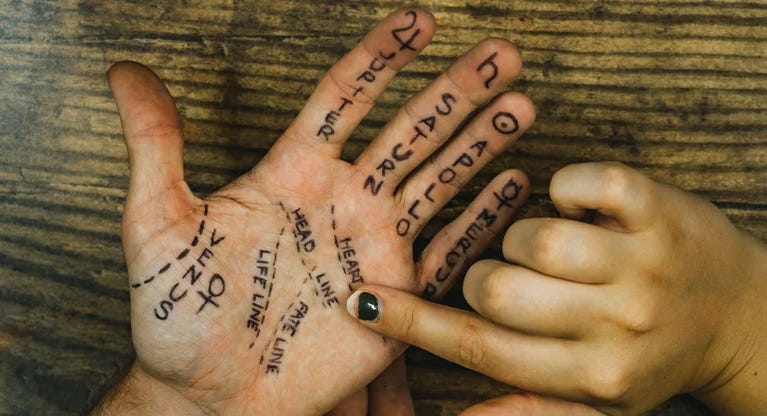

Perhaps the most famous anecdote linking a Roman figure to palmistry involves Julius Caesar. Historical accounts and legends suggest that Caesar placed considerable trust in the art. He was said to have judged the character of his men by examining their hands, looking for signs of courage, loyalty, and determination.

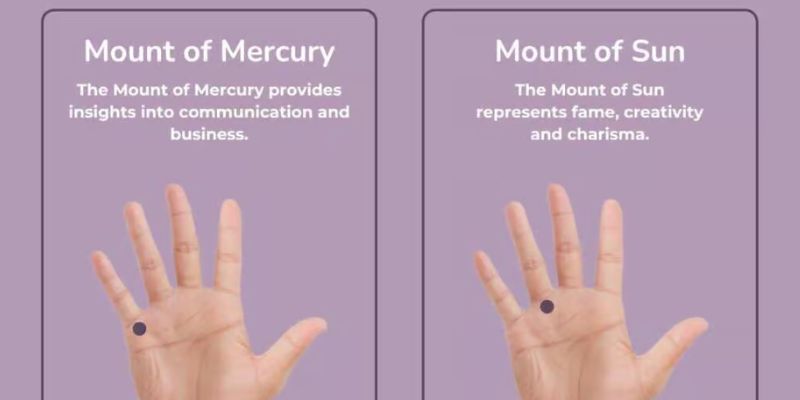

While likely embellished over time, the story highlights a key aspect of Roman chiromancy: its use as a tool for personnel selection and character assessment. In a world of shifting alliances and political intrigue, any method that promised insight into a person’s true nature was invaluable. A firm hand with a long, clear Head Line and a strong thumb (the seat of willpower) was considered the mark of a natural leader and a trustworthy officer.

What the Romans Looked For

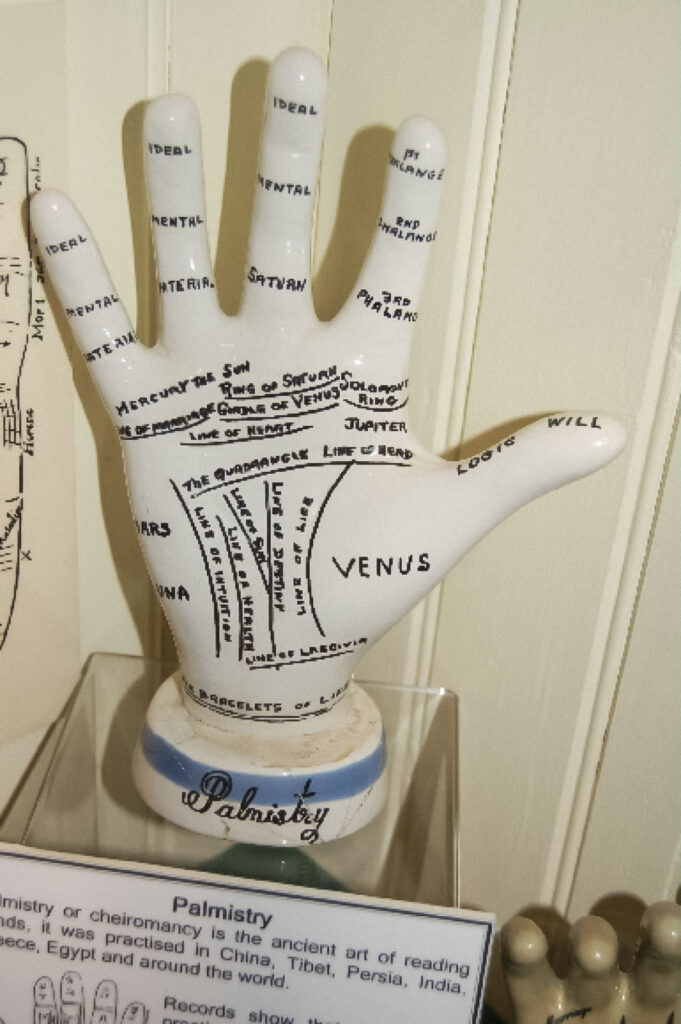

Roman palmistry was likely more straightforward and less mystical than its Eastern counterparts. The focus was on tangible qualities that were valued in their society:

- The Life Line (Linea Vitalis): As in other traditions, this was not about lifespan but about vitality and fortune. A deep, unbroken line was a sign of good health, physical strength, and the favor of the gods—essential traits for a soldier or politician.

- The Head Line (Linea Naturalis): This was of paramount importance. It represented a person's intellect, rationality, and mental clarity. A long, straight Head Line was the mark of a brilliant strategist and a logical thinker, qualities highly prized in Roman leaders.

- The Heart Line (Linea Mensalis): While it related to emotions, for the Romans it was also an indicator of one's integrity and moral character. A clear Heart Line suggested an honorable and reliable individual.

- The Girdle of Venus: This curved line above the Heart Line was often viewed with suspicion. It was associated with a lustful, decadent, and unreliable nature—qualities that could undermine the strict Roman virtues of discipline and duty.

A Private Art in a Public World

Unlike the public spectacle of an augury, palmistry was a private consultation. It was a one-on-one practice, often conducted by “Chaldeans” or “mathematici”—a general Roman term for astrologers and diviners from the East. While some conservative Roman writers like Cicero were skeptical of such practices, their popularity among all classes of society, from slaves to senators, is undeniable.

People would consult a palmist not just to understand their own potential, but also to assess rivals, business partners, and even potential spouses. It was a practical tool for navigating the complex social and political landscape of the Roman world.

Conclusion: The Palm as a Reflection of Roman Virtue

Palmistry in the Roman Empire was less about mystical prediction and more about a practical assessment of character. The Romans saw the hand as a reflection of the qualities they valued most: strength, logic, honor, and willpower. It was a mirror to a person’s innate virtue (virtus), their potential for greatness, and their capacity to lead and endure. In the lines of the palm, the Romans sought not a glimpse of the future, but an understanding of the unchangeable nature of the soul.